Down with NDR

March Capital Markets Roundup

I’m back

And I’m here to remind you that not all net dollar retention is created equal.

In my June 2020 piece SPF Infinity I covered how:

We…discovered 35 different ‘names’ for retention. Parsing through the 35 ‘names’ we found there are really just 3 types of retention (obviously) - net & gross dollar, and user retention - with net dollar being the most popular disclosure. But there are 23 different ‘names’ for net dollar retention...[and] the companies that agree on which retention metric to report do not agree on how to calculate that metric.

Not all net dollar retention is created equal.

That much is now obvious.

But this isn’t just due to the name or formula used to describe and calculate net dollar retention. This is because net dollar retention tells us nothing about a company’s margin on expansion or a company’s ability (or the cost) to innovate.

Free growth, and growth vs. sustaining expenses

There is no such thing as free growth.

But, raise your hand if you’re guilty of perpetuating the fallacy that “with 150% net dollar retention, XYZ could turn off sales & marketing tomorrow and still grow 50%.”

While I anxiously await for someone to share an old tweet or blog post where I’ve fallen prey to this trap myself, let me explain why this is indeed a dangerous fallacy.

I think of software P&Ls as having two distinct layers: a “sustaining” P&L , and a “growth” P&L . The general idea is that for any value activity a software company performs resources are either going towards retaining existing customers (sustaining) or to selling new customers (growth). This is very aligned with how the world of software was explained by Travis Cocke in How to Be a Value Investor in Software.

How do I visualize this?

I can’t really - it is unrealistic to expect any company, public or private, to segment out all of their costs and expenses, especially headcount costs. Even if they tried the exercise would simply be too gameable and non-GAAP for anyone to take seriously.

That said, Cocke does do a terrific job at outlining how and why to contemplate growth vs. sustaining expenses in costs of goods, G&A, sales & marketing, and product & engineering (I won’t do him the disservice of ruthlessly smashing Ctrl-C + Ctrl-V - his whole piece is worth reading). The summary is that for any of the aforementioned activities, there are resources (people, services, etc.) that can be focused on different customers (new and/or existing customers), and both customers require expenses.

So, theoretically then, we must take it that retention of any kind - logo retention, and gross or net dollar - also costs an organization something, and those costs are likely present in the sustaining customer success, account management, and product & engineering expenses (salaries associated with maintaining platform / old features, etc.) as well as in sustaining cost of goods (support headcount for existing customers).

But we never really get to know what a company’s margins on renewal/expansion sales is. We just get to hear that customers are buying more! And we eat that growth up.

There is no NDR Margin

In some models (i.e. outbound sales, large enterprise deals with per seat pricing, vertical software selling new modules into a customer) I theorize net expansion is far less profitable than with say, a Snowflake (usage model). My colleagues at OpenView, Sanjiv Kalevar and Kyle Poyar, did a terrific job at articulating Snowflake’s advantages in a recent series of posts and a set of materials on usage based pricing:

Investors especially love how the usage-based pricing model pairs with the land-and-expand business model. And of the IPOs over the last three years, seven of the nine that had the best net dollar retention all have a usage-based model. Snowflake in particular is off the charts with a 158% net dollar retention. But JFrog, Fastly, Elastic and Datadog all have north of 130% net dollar retention as well.

A usage based model is like a seed planted outside. Once it is in the ground, you don’t do a lot. Customers (nature) take care of the growing. Contrast this with seat or product-based model selling into enterprises that takes constant resources (nurture) deployed against it to implement / train and then sustain growth - each and every one of the dead succulents on my desk can attest to my failure to deploy any resources (account management, customer success, and others) against sustaining them.

The way that companies with usage based models structure the components of their value activities (roles within sales & marketing, pricing, way the product team is structured and the product itself then built) aligns well with driving “free growth”.

There are still costs required for account management, customer success - but the costs are less, because to get a Snowflake customer to use more Snowflake they just… use more. To get an Anaplan customer to buy more seats, the company spends a lot of money on customer success, account management and of course sales people who get paid commissions, etc. Similarly, some companies have entire sales teams & BDR teams dedicated to account expansion (i.e. Qualtrics, I believe). In that case there's account expansion that essentially looks & feels like new business and then there's account expansion that looks & feels "organic" (like usage-based growth) - but it isn’t.

Not all net dollar retention has the same margin.

But that isn’t all.

When did we forget about innovation?

LTV/CAC metrics are also mostly bullshit, because the LTV is based on gross profit & churn, which excludes the cost of ongoing product development which is necessary to avoid competitors overtaking your product & your users churning off en mass...There is a popular notion hot fast-growing software companies that are losing money are doing so because they are "investing through the income statement", spending $ to acquire customers, & R&D on new product features. Investors believe losses reflect investment not competition.

This is the other important point that the focus on net dollar retention and its impact on growth obscures: companies must keep innovating to maintain market leadership!

Focusing on net dollar retention alone, and abstracting efficiency into any SaaS go-to-market metric ignores the investment in innovation (product and engineering) that is also required to drive that continued expansion and maintain competitive advantage.

Where do any of these SaaS metrics contemplate the cost of product & engineering?

Burn productivity & strategic insights

There is a solution.

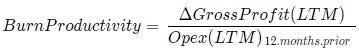

Burn productivity which is written about in detail by King Goh is the perfect metric for measuring both the efficiency of the go-to-market investment in business growth, the sustaining sales & marketing expenses, and the cost of continued innovation (I call it return on incremental invested capital, and in 2020 we expanded on this in our SaaS benchmarks report - but credit goes to Goh for the application to enterprise SaaS).

Here is how to think about what this metric gets at:

A company’s competitive advantage(s) is (are) fleeting: unless the tech is remarkably difficult to replicate someone can (and often will) come and build the same mousetrap and sell it for less (I’m oversimplifying, but kind of). Yes, I acknowledge that switching costs, distribution advantages, and network effects are all real and powerful phenomena - but I also recognize unless you’re expanding on the customer needs you address, someone can probably match competitive advantages and take share.

Take the graphic below from "Strategic Insight in Three Circles.”

If NewCo’s value proposition (the value of the needs addressed in A and B) and competitive advantages (the points of difference in A) are net valuable to customers in their target segment (A > C) then NewCo is probably going to win over competitors.

But just for today. NewCo needs to continue spending to create (1) sales with new customers, (2) renewal sales, and (3) new products, features, and functionality to sustain A today and also grow A into E, the customer needs white space.

NewCo becomes an enduring enterprise when it can defend A and expand it to address new needs over time in a way that remains differentiated vs. competitors offerings.

(E): White Space

I’ve written before that the economic profit of software companies - the spread between the cost of capital and the return on invested capital - is so huge, that poor capital allocation decisions are obscured today. If this is true (it may not be!), simply looking at an arbitrary rule about the sum of growth and profit, rules of thumbs about how much more customers buy between periods, or the efficiency of overall sales and marketing don’t tell us much at all. We should instead be asking “what is the efficiency of the spend a company drives into sales, marketing, product, and engineering” or “how strong is a company’s competitive advantage, and how well are they defending that”. Especially if software companies are just penetrating white space.

“The markets are larger than we ever expected.” A lot of businesses - especially SaaS - are in fact penetrating a vast expanse of white space. And because white space is really what companies are after, we need to measure not just how well a company sells or expands, but the effectiveness of all activities that help a company fill that white space.

In other words, de-emphasize the focus on sales and marketing efficiency, and focus on the true profitability of expansion (the way the organization is set up to sustain existing customers), and a company's ability to extend competitive advantage via innovation. The combination of resources - across sales, marketing, product, and engineering, and the culture that allows constant innovation and produces results for customers matters. Take the following commentary on Elastic as an example of this:

Looking at NDR? Tread more thoughtfully.

Just as no single definition of net dollar retention is exactly alike, no application of a company's resources are alike, and therefore, abstracting and then benchmarking across the landscape of public SaaS companies can be dangerous. I’m all for benchmarks - but the simplest way to explain things tends to be “the higher the better” on all figures: growth, gross margin, free cash flow margin, net dollar retention, and CAC Payback (ok this one is lower is better but you get it).

Focusing too much on great numbers today (or where this number compares to other companies doing different things in different markets) without an appreciation for the long term potential margin profile for a business given its own nuances is dangerous for companies and investors alike. This new, shiny metric of net dollar retention has become a convenient one for companies to tout and it is rewarded by investors, but it is non-GAAP and highly gameable (per my 2020 post). Further, NDR doesn’t always paint an accurate long term picture of what it will cost for any given organization’s customers to behave in that way over the long term - especially as companies have to sustain and innovate products for customers to buy, which it completely ignores.

I love NDR - but don’t sleep on the big picture.

What Else I’m Reading

Growth Unhinged (by Kyle Poyar) and Rak’s Facts (by Rak Garg).

Special thanks to my colleague Tom Kenyon for his reviews of this post.

Incredible work. Thank you. If I were your intern today, what would you have me read to develop a deeper understanding of frameworks as you detail in the blog ?